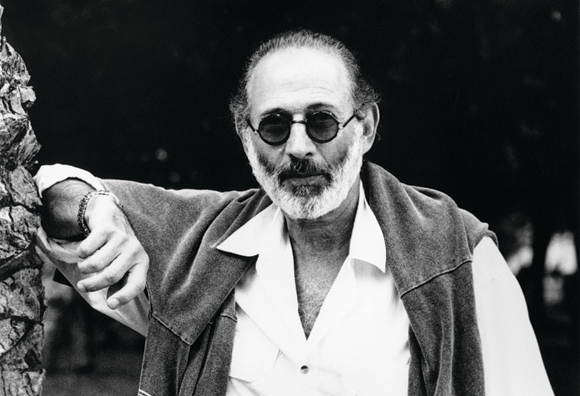

What triggered your decision to move on from taking photographs of Hollywood stars and celebrities to actually making your own films?

Money (laughs). No, seriously, I don’t think there was a ‘moment’ as such, but there was a time where I started thinking about making a film. It is very naïve of me to say that, and more so to actually do it, because once you are on set, they shout things like, ‘Get the best boy!’ And you think, ‘What the hell is a best boy?’ I didn’t know there is a different language to it. I ran around the set not knowing any of this, but I had some really great help. I became very friendly with my cameraman before I started. I hired someone whose work I really liked, so I did not have to spend all my time telling him what I wanted, because we understood each other. Faye [Dunaway] was very helpful too. In fact, all the actors were great. In order to make a film, you need to hire really good people. When someone asked me, ‘What do you do as a director?’ I struggled. I thought, ‘Well, what do I actually do?’ But then, I do everything, because I have to approve everything. Like Truffaut said, ‘All the questions keep coming to you. And you have to answer them.’

Your films, especially Puzzle of a Downfall Child, are very European in spirit. You seem to have been influenced by the New Wave. Did you consciously look for inspiration in European cinema at the time?

No, I didn’t consciously … but subconsciously, obviously. I didn’t even start seeing European films until I was into my career as a photographer. I went to the movies a lot when I was a kid, but back then people like Mickey Rooney were my heroes.

But if you ask me who influenced me, that is something else. It’s true that I was influenced by the Beat Generation and the New Wave in terms of their thinking, their revolutionary spirit. I think I was, and still am, influenced by a certain respect that I don’t find in people who run big businesses. I worked with these people and had some awful experiences. And models are like actors, they are really totally naked in front of you – they give you everything. But when big businesses think they need a new face, they just dismiss the old one. So they have sent these girls all around the world in first-class planes, first-class hotels and from one day to the next, they are nothing to them. I am very fortunate, because I have two careers, and when the studio bosses say, ‘Well, we don’t really want you,’ of course I will keep trying to get my films made, but my photographs pay me a lot of money and that is what I lean back on.

Does this partly explain why you took a break from filmmaking since 2000?

Even when I was making films, six or eight years would go by, because I usually work on five or six projects at a time. I could be working on one screenplay only, but if the studio doesn’t like it, then I have wasted two years writing something. I am currently working on four different projects. One is that after my last film I made a conscious decision to organise my photo archive, because I left it all untouched in a barn up in the country for about 30 years. I really thought that it would be totally destroyed, but it’s not. People spend lots of money on storing their photographs in air-conditioned places, I think the best way is to throw them in a barn and leave them there. They will preserve themselves. But I’ve decided to organise the archive now, so I have staff scanning and retouching everything, because I am offered lots of exhibitions all over the world, and I want that to be one of the things people remember. I like my photographs now. I don’t always like my work when I do it.

Apparently, you are also developing a sequel to Scarecrow.

Yes, I have written a sequel to Scarecrow, and any European who likes my films thinks, ‘Wow, what great idea!’ But in America they say, ‘No, we want Iron Man.’ I understand that. I will still get it made somehow, but my problem is that the big studios don’t want to do it, so I have to figure out a different way to get it made. And Gene Hackman doesn’t want to work anymore, so I have to find a substitute for him. And Al, I would love him to do it, and I will see if he is interested, but I know his agents are going to say, ‘Well … it’s not going to make a lot of money.’ When I saw him about a month ago, I gave him the script and he said, ‘I’ll read it.’ We will see. If Al would say he likes to do it, then we’ll find a way.

In your films, but also in your photography, you seem drawn to the street and the characters inhabiting it. You are even credited as the man who has brought fashion photography out into the streets – the streets of New York in particular.

I was brought up in the Bronx which allowed me to understand the rich and the poor; I was able to travel through both. In New York you fight your way through a lot of things, but I don’t mind. I am a New Yorker. I like New York, and I always liked hanging out there. I have done about seven films in Hollywood, but it never intrigued me to be part of that community. It is a film community, a different world. You go to a supermarket and people there hand you a script they would like you to read. At the airport, they give you a script they would like you to read, because everybody is in the film business over there. New York is much more anonymous, and I like that. I like walking the streets … I see all these personalities travel to festivals with sixteen bodyguards and all that – is that the way to live? Not for me. And I hope my work reflects that.

What’s the secret behind your photography? How do you seduce people to make them show their inner sides?

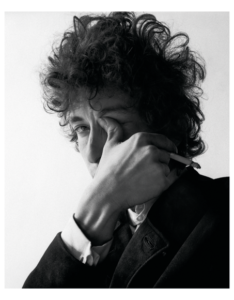

I drug them (laughs). No, really, I think it really just depends on the person you have sitting in front of you. Sometimes you get along with them, sometimes you can’t get along with them. I was certainly lucky with Faye, and she called me to do particular shoots, because I had already done some photographs of her. And Bob Dylan, for example, I had been aware of him through Nico from The Velvet Underground, she was a friend of mine. And another friend kept telling me about Dylan, Dylan, Dylan. Finally, I listened to his music and I said, ‘I love this guy.’ But even then I didn’t make contact with him. Then one day, I was working in my studio, and I remember that a rock and roll journalist was there and a disc jockey, so I must have been doing something with a music personality, but I don’t quite remember who it was. They had just seen Dylan and I said, ‘Next time you see him, tell him I’d like to photograph him.’ The next day his wife called me and she gave me the address of where they were recording. His wife was also one of the people who told me about him years ago; I knew her before. So I came to him with a certain trust, which was important because he has always been very suspicious of the press, and rightly so. I understand him, because I have had my own experience with that.

Has there been a certain incident?

I once had a woman from the UK who wanted to interview him and she came to me on the mere pretence that the editor of Queen magazine wanted me to photograph her. And I did it, and while I was taking the pictures, we talked about her. She told me that she had just done an interview with Marlon Brando and so on, and then she said, ‘You know Bob Dylan, right? Can you get me an interview with him?’ I said, ‘Oh, I don’t know.’ But then I told him the whole story, and I said, ‘It’s up to you, do you want to do the interview?’ He said, ‘Okay, I’ll do it, but you’ve got to come along.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll come along.’ So we went to Dakota to do the interview and the first question was, ‘Well, now that you’re famous, how much money do you want to make?’ And he said, ‘All of it.’ And the whole interview went like that. She asked him, ‘Do you believe in nature?’ And Bob would say, ‘No, I don’t believe in any drugs.’ I would love to find that interview; maybe it still exists somewhere, maybe it was never even published. In the end, it turned out she was a real con artist. Her father was a munitions man and he would follow her all over the world to pay off her debts. She was also living in a friend’s apartment at that time, but she didn’t have any money, so she sold the paintings from that apartment. She was a real number.

What’s your relationship with Bob today?

I haven’t seen him since 1973. He is on the road a hundred days a year, I am doing my thing. He knows what I am doing though and I am in contact with his management all the time, because they are in New York and they use my photographs.

There is also a striking photograph of Roman Polanski that you shot before he became famous?

Yeah, I met Roman at the Lincoln Centre on the night that Knife in the Water premiered at the New York Film Festival in 1963. I remember I had a broken leg, so I waited there until everybody had left, so I could come down the escalator quietly. Roman was standing there with his producer, and he really charmed me. He was this little pixie. I went over to introduce myself and told him that I would like to photograph him. At that time, I was also involved with some nightclubs in New York, and Roman loves to go out. He loves to party and all that. So we became great friends.

You also seem to have a good sense for discovering great talent for your films, such as Al Pacino and Faye Dunaway.

I didn’t discover Faye, and I didn’t discover Al. Al was doing very well in theatre before I met him. I saw him on stage, that’s where I discovered him. He was great, and I was fortunate enough to get him for my film. Morgan Freeman was around for 30 years doing theatre and a children’s programme on public television, but I didn’t know him then. When he came in for the interview, I simply fell in love with him just by his personality, his attitude. In the middle of the interview, he just reached down into his bag and pulled out a banana and started eating it. I thought, ‘This is the guy I want!’ He wasn’t my character, nothing near to the guy in the script, but I went home and told my wife, ‘I met an actor today who I really love. I will have to change the part completely so that he can do it, but I want him.’ And I did that, and that is how everybody got to know Morgan Freeman. It’s the same with my photographs in a way. I had an exhibition of Bob Dylan photographs in Paris about five or six years ago. On the opening night, an actor came over to me and said, ‘Boy, you were there at the right time.’ And he is right. Would I want to photograph Dylan now? I think it would be a great challenge, and I don’t really want to photograph him now. I don’t see the same thing that I saw back then. But it is the same with him. A few years ago, I saw him in an interview on Sixty Minutes where they asked him, ‘How did you write all those songs?’ And he said, ‘I don’t know. I couldn’t do it today. I am something different today.’

You’ve got another exhibition in Paris coming up in November. What are you going to show this time?

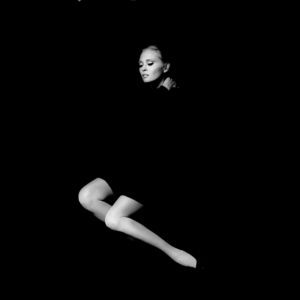

There will be work that has never been seen, along with some well-known photographs. It is not an enormous gallery, but it is a very good gallery, in a very good spot: Rue de Seine. It is a real challenge trying to figure out how to hang it though. You start off wanting to show so much, but you have to keep cutting down, because today they like seeing large-scale prints. The gallery owners saw some of my personal pictures from travelling and some photographs that I used to think were just snapshots that I took on my farm. They got so enamoured by these pictures that it made me look at them again, and I realised these are actually good photographs. I will have a whole wall of these in the show. But it will be half and half. Bob Dylan occasionally, Faye Dunaway, Catherine Deneuve, a beautiful image of Charlotte Rampling, which I haven’t really shown that much. I shot it right after she did Georgy Girl, when she was really young in her career. She is beautiful in it.

What makes a good photograph for you?

When I go out and shoot something, my eyes see something and I snap it. I just go out and take it. Other people look at it and they might see more in it than I do. Like with my films, if you ask me the intellectual interpretation of them, I won’t give it to you, because other people will say things that I had no idea of. But yes, it is just what I instinctively see as a photograph. I capture my interpretation. And I hope what amuses me, amuses other people, too.

Exhibition: La Galerie Seine 51

Paris, 7 November – 14 Dezember 2013