Mickey Rourke has a confession to make. But first he allows himself a little smile. „It’s all new now“, he says with a faint suggestion of his trademark impish grin hovering about the battered face. „It’s almost like I never had a career before.“ Ensconced today in London’s ultra-exclusive Blakes Hotel, Rourke is talking about his comeback in Darren Aronofsky’s low-budget marvel called The Wrestler, and how the film has opened an entire new chapter in the 52-year-old actor’s troubled life.

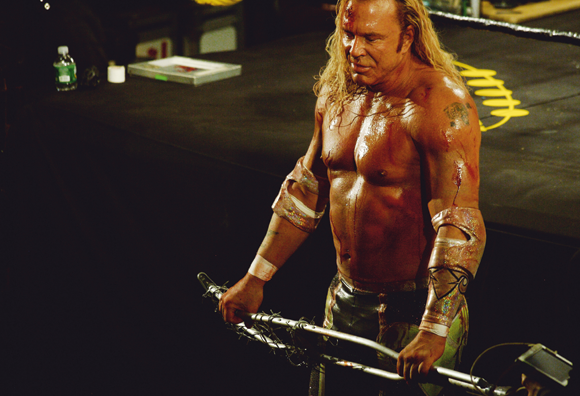

In the film, he plays Randy ‚The Ram‘ Robinson, an over-the-hill fighter who was a wrestling star in the eighties but now lives vicari-ously through his past. It’s his first leading man role in, well, ages, and it seems tailor-made for Rourke, the man who was tipped as Hollywood’s ‚next big thing‘ when he set the screen alight as Matt Dillon’s charismatic older brother in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1983 Rumble Fish, and countless female hearts aflutter ever since feeding a blindfolded Kim Basinger in front of her fridge in 9 ½ Weeks – if he hadn’t had that tendency to make life difficult for himself. Thus the fallout from his repeated, determined attempts in the past to jeopardise everything good, has been painful to watch and exhaustively chronicled – namely two decades of personal and professional ostracism after a series of half-witted movie choices, street scuffles and violent tantrums on set, intermitted by a calamitous foray into professional boxing that involved smashed knuckles, broken ribs, two concussions, a split tongue, several facial injuries and half a dozen operations to repair the damage – hence the mangled look. There were also some matters of his six-year marriage to the model Carrie Otis, whom he met on the set of the forgettable semi-porno, Wild Orchid. You may have read about this, too.

Today, however, at an age when most actors would be content to sit back and bask in the memory of their best works, Rourke is having a one-man renaissance. Too late to be a mid-life crisis, and too prolific to be a final fling, he eventually seems to be finding his feet again as a box office force to be reckoned with. The Wrestler has been universally lauded ever since it won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival last September, and it’s thoroughly deserved: to the envy of his peers, the man has an innate talent that no amount of tuition can teach and no deluge of publicity can buy. Put simply, he’s incapable of being anything but hugely charismatic on camera. That said, the charm offensive continues in the moment of meeting Rourke in person, he somehow manages to intoxicate the room. He is amiable but wary, his body tensing and his eyes welling up every time the conversation skids in the vague direction of his past and the misery he has brought upon himself. In fact, he doesn’t actually talk as much as pour forth. „When you have a career and then you ruin it, you know, people don’t fucking rush to put you back to work,“ he sighs. „And, you know, I wasn’t a little bit bad. I was fucking horrible for fifteen, sixteen years. I was really out of mind, out of control. I had to lose my house, my wife, my money, my career, my… it took everything for me to fall all the way down to the bottom… and I have no-one else to blame but me.“ After more than fifteen grim years in Hollywood exile, he knows that it’s impossible to talk about a comeback without discussing what he is actually coming back from, and he certainly doesn’t mince words. But talk about The Wrestler and he’s funny, passionate, mostly engaged if occasionally distracted by a pretty blonde, „That’s Loki, sixteen and a half, she’s just had a stroke… but she’s hanging in there.“ He eventually introduces his pet Chihuahua who obediently marches over and collapses on a pillow besides him.

Loki’s abiding attitude rather fits the mood of The Wrestler. Hunched, puffed-up, half-deaf and tortured (at one point literally, in a gruelling bout played with frightening dedication), Rourke embodies a man struggling to move his own damaged bulk around. He might be an ultimate loser, but he’s a survivor too, still working on the small-time circuits for a fistful of crumpled dollars and a fraction of the glory. When he suffers a heart attack, he makes an honest attempt to retire from wrestling and to re-establish relations with his estranged daughter, but as soon as things start taking course he can’t help but screw up again. Much like Robert De Niro once pumped himself up to an enormous weight for his Oscar-winning turn as Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull, Rourke put on 35 pound in muscle, lifted weights twice a day, visited tanning salons and relentlessly fought his own natural boxing instincts to look every inch the part. „Being trained for years to throw punches that you can’t see and move in a certain way, it was really hard for me to break this,“ he recalls. „But then I thought, fuck it, if I am gonna do this movie I wanna look just like these cunts to do it. In the end, I really wanted the approval.“ What’s most impressive, though, is that he lends his character a certain rumpled dignity, that comes right from the heart, and is at times harder to watch than any of his own stunts: „You live in what my doctor calls ‚a state of shame‘. I was ashamed I lost my wife more than anything else. Not the money, it was the other things that come along with it… when you become a failure because you self-destruct, and when you live, for so many years, in like a state of hopelessness like Randy ‚The Ram‘.“ It is that kind of pathos that is infused in almost every scene in The Wrestler, leaving a moved audience wonder what would have become of the promising young actor and his great sense of taut energy mixed with that undercurrent of softness and vulnerability if he had observed Hollywood’s rules.

After bursting onto the scene with his breakthrough role in 1981’s Body Heat, Rourke managed to make a quicksilver feint away from jobbing as a bouncer at an L.A. transvestite club to the Hollywood A-list. Soon after Barry Levinson’s Diner introduced him to the world, followed quickly by starring roles in Rumble Fish, The Pope of Greenwich Village and Year of the Dragon and opposite Robert De Niro in Angel Heart. It was an astonishing departure for the young actor who came up through the famed Actor’s Studio in New York, and Rourke made the most of the techniques he had learned and the charisma he radiated until his promising star-power started to isolate him ½ Weeks came out and made him the sexiest man in the world for a season. Despite showing off an increasing on-set volatility since the late eighties and openly blaming studio chief Sam Goldwyn Jr. for the failure of the 1987’s IRA thriller A Prayer for the Dying, Rourke is said to have turned down big parts in blockbusters, everything from Platoon to Silence of the Lambs, and instead made increasingly bizarre role choices, wobbling between dud lead roles (Desperate Hours, White Sands) and some unalloyed stinkers in the likes of Harley Davidson and The Marlboro Man, and that, as they say, was that. But what went wrong? There’s a heavy sigh accompanied by a very long drag from his Marlboro Red. „I simply knew nothing about the business or politics“, he says. „I came from a violent background … and I had gotten very hard. For several years, when I was a student, I let go of that, but when I started to become successful in the business it came back. Because I resented the fact that people were treating me special for being in the movies. I still remembered the old days when I was washing dishes, and collected money for gamblers, and worked as security in whorehouses and bars… and now they were buying me dinner and drinks and clothes and whatever, even though I had the money, and a fucking big house and the pussy, and anything anybody can want. But they were kissing my ass, and I couldn’t stop it. And, after a while, I got really upset about it. I just didn’t want any of it.“

Miami after his father walked out the house when he was six years old. His mother remarried a Miami Beach cop who used to beat him and his little brother Joe, but his mother „allowed him to do it”. Even though he can’t quite bring himself to admit it outright, he eventually reveals that it was to a large extent the struggle with his damaged background and his psychological wiring that he tried to compensate through his tough-guy persona and that then exiled him from an industry no longer willing to put up with his tantrums. „It’s true, I had some shit happen when I was little, that I was really, very terribly ashamed of, and that made me feel very insignificant and small and unimportant, and I had brought that with me,” he pauses again. „Then, I had to come to terms with all these people, producers, directors… anyone but the man who was kicking the fuck out of me and my brother for a decade […] But I didn’t have the knowledge to fix what was broken, you know. I need to talk to somebody who knew what makes one grow a man,” he says, referring to his therapist in Los Angeles, who helped him deal his issues and to turn his life around.

It seems that the mismatch between his skewed manliness and ingrained vulnerability is not only the source of all the conflict and confusion in his private life, but also at the core of Rourke’s on-screen appeal; that perhaps he was just never able to strike the balance between the two. Seen from this angle it even makes sense that at the beginning of the nineties Rourke made that decision to semi-retire from acting, which he then scorned as a ‚womanly profession‘, and to revert to boxing, his teenage passion, hoping to finally find peace in the ring, and submitting himself to the rigorous training, abuse and combat that would eventually pay off in The Wrestler. But even today there is still a cunning edge to him, too – an almost imperceptible flicker of some gloomier, nervier energy that pulses just beneath the calm, gentle exterior.

Darren Aronofsky’s decision to pick Rourke to play a man in search of redemption through repentance, could seem vicious to some, but merely demonstrates the increasing aura of goodwill that has illuminated the actor in more recent years – no matter how defiantly he was scraping barrel bottoms. For every tantrum, bust and bad movie, it seems, there has been a Hollywood knight disposed to save him from the worst: Francis Ford Coppola who gave him a modest role in Rainmaker; Sean Penn who put him opposite Jack Nicholson in a short but sharp scene in The Pledge; Sylvester Stallone who got him aboard the 2000 US remake of Get Carter (only because Stallone paid part of Rourke’s fee out of his own pocket, Rourke admits); Robert Rodriguez who ensured Rourke’s re-introduction to mainstream audiences as Marv in Sin City, a part that captured Rourke’s late-blooming, defeated anger covered under layers of make-up and-band-aids.

And yet, who in their right mind would have ever pictured Rourke headlining a wrestling movie? No-one – least of all Rourke himself. „I never had any love for wrestling. To me it was just a sport that…morons went to,“ he smirks, but then tucks away that smile and tenses up again. Of course, wrestling isn’t really the thing in The Wrestler, at least not as the kind of antique B-genre exploited in the Coen brothers’ Barton Fink, and if anyone knows that, it’s Mickey Rourke. A wish to set the record straight, however, might explain why he then insisted on rewriting all his own dialogue in The Wrestler and make it seem almost biographical in the end. „The stuff that comes out of my mouth was stuff that’s very personal, stuff that I have been through…that’s the part of me that is in there.“ He pauses, then beams that familiar grin again: „I mean I was glad I was making a movie and nobody really thinks I was talking about myself.“